Threaded fasteners are fundamental mechanical parts designed to firmly connect two or more components using matching threads. They are indispensable across countless industries as they provide reliable joints that hold structures and machinery together. In this blog, let’s learn everything about threaded fasteners, covering the definition, working principle, types, advantages, uses, materials, and comparison with non-threaded fasteners.

What Are Threaded Fasteners?

Threaded fasteners are essential hardware components that create secure joints between objects by utilizing interlocking helical threads. Unlike permanent joining methods like welding, they are designed to connect parts in a way that can often be adjusted or undone when needed. The defining feature of these fasteners is their threads—spiral ridges that allow them to mate with another threaded component, such as a nut or a pre-threaded hole. They are made from various materials to suit different applications, ranging from everyday carbon steel for basic uses to stainless steel and high-strength alloys for environments where corrosion resistance or extreme durability is required. Threaded fasteners are used in everything from large-scale construction projects, like bridges and pipelines, to small consumer goods, such as electronics and furniture, making them one of the most widely used mechanical parts globally.

What Are the Advantages of Threaded Fasteners?

- They provide excellent clamping force, creating strong and secure joints that are reliable for high-stress applications.

- They offer adjustability, allowing you to tighten or loosen the joint to achieve precise alignment or tension as needed.

- They are highly versatile, available in a wide range of sizes, materials, and designs to suit almost any application or industry.

- They enable easy assembly and disassembly, making maintenance, repairs, and modifications simple without damaging the connected components.

- They can be enhanced with thread-locking compounds or self-locking nuts to prevent loosening from vibration or dynamic loads.

- They distribute load evenly across the joint, reducing stress on individual components and improving overall structural integrity.

- They are compatible with international standards (like ASTM, ISO, and DIN), ensuring consistency and interchangeability globally.

- They can be customized with different coatings (like zinc plating or hot-dip galvanizing) to resist corrosion in harsh environments.

Typical Applications of Threaded Fasteners

- In construction, bolts and threaded rods secure steel beams, concrete structures, and building frameworks to ensure structural integrity.

- Automotive manufacturers use screws, bolts, and nuts to assemble engines, body panels, and interior components, with self-locking nuts preventing loosening from vibration.

- In the oil & gas industry, studs and high-strength bolts connect pipe flanges and drilling equipment to withstand high pressure and harsh environments.

- Electronics manufacturers rely on small machine screws to assemble circuit boards, casings, and components with precision.

- Furniture makers use wood screws and bolts to assemble chairs, tables, and cabinets, allowing for easy disassembly for moving or repairs.

- Aerospace engineers use fine-threaded fasteners (like UNF) to assemble aircraft components, as their high load-bearing capacity ensures safety at high altitudes.

- In industrial machinery, studs and bolts secure heavy components like gears and motors, providing the strength needed for continuous operation.

- DIY enthusiasts use self-tapping screws and bolts for home improvement projects, such as installing shelves, hanging fixtures, or repairing appliances.

- Marine industries use corrosion-resistant stainless steel bolts and nuts to assemble ship hulls, decks, and equipment, as their material resists saltwater damage.

- Medical equipment manufacturers use precision screws to assemble devices like surgical tools and imaging machines, where accuracy and reliability are critical.

Tips for Using Threaded Fasteners

- Always choose the right material: Use corrosion-resistant materials (like stainless steel) for outdoor or wet environments to prevent rust and failure.

- Match the fastener to the load: Ensure the fastener’s strength rating (e.g., Grade 5 or Grade 8 steel bolts) exceeds the anticipated load to avoid fatigue or breakage.

- Lubricate when tightening: Applying lubricant to threads reduces friction, ensuring consistent clamping force and preventing cross-threading.

- Use the correct tools: A torque wrench ensures precise tightening—over-tightening can break the fastener, while under-tightening leads to loose joints.

- Avoid cross-threading: Align the fastener with the threads and turn it by hand a few times before using tools to prevent damaging the threads.

- Use washers: Always use flat washers to distribute load and protect components, and lock washers or self-locking nuts for applications with vibration.

How Do Threaded Fasteners Work?

Threaded fasteners work by converting rotational force (torque) into clamping force, which holds connected components tightly together. This process relies on the interlocking of male and female threads: when you turn a threaded fastener (like a bolt) into a matching threaded part (like a nut), the helical threads act like an inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder, making it easier to apply the necessary force to create tension. As the fastener is tightened, the bolt stretches slightly (this is called preload), and this stretching pulls the two components together, creating a strong clamping force. The friction between the mating threads, as well as between the fastener’s head and the surface of the component, prevents the fastener from loosening on its own. Proper tightening is crucial—too little torque leads to insufficient clamping force (which can cause the fastener to fail from fatigue), while too much can stretch the fastener beyond its elastic limit, breaking it. Lubrication can help ensure consistent tightening by reducing friction, making the conversion from torque to clamping force more reliable.

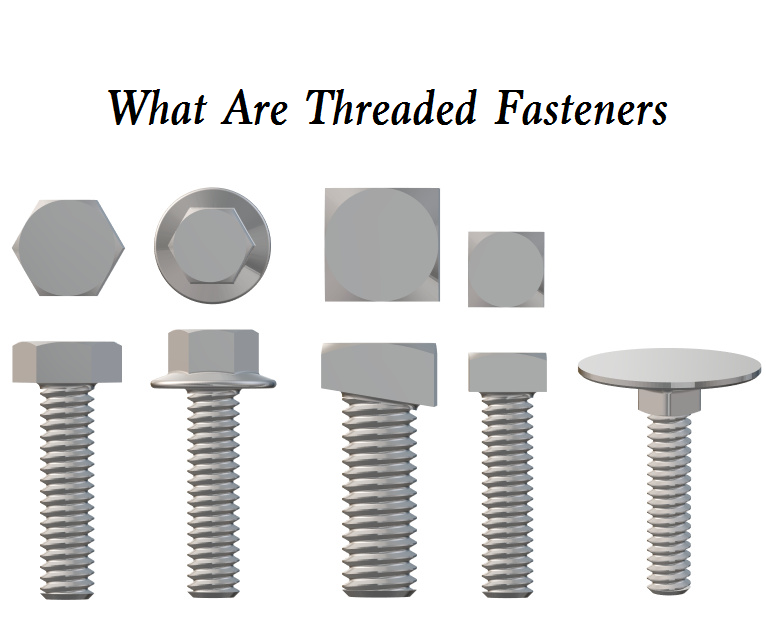

Common Types of Threaded Fasteners

1. Bolts

Bolts are externally threaded fasteners designed to be used with a nut to create a joint. They do not tap their own threads, so they require a pre-threaded nut or hole. Bolts come in many specialized types: carriage bolts have a square shoulder under the head to prevent rotation when tightening the nut, lag bolts (or lag screws) are long, thick bolts with a pointed end for driving into wood, and machine bolts are precision-made for use in machinery and equipment. They are typically made from steel, stainless steel, or specialty alloys, and their ability to distribute pressure over large areas makes them ideal for structural applications, construction, and heavy machinery.

2. Screws

Screws are versatile threaded fasteners that can either tap their own threads (self-tapping screws) or be used with pre-threaded holes. There are many types tailored to specific materials and uses: wood screws have sharp threads for gripping wood fibers, sheet metal screws have finer threads for attaching thin metal sheets, and machine screws are smaller, precision screws used in electronic and mechanical assemblies. Common head styles include Phillips (cross-shaped), flathead (countersunk for a flush finish), and Robertson (square-shaped for better grip). They are driven using screwdrivers or powered tools, and their ability to create secure joints without needing a separate nut makes them popular for DIY projects, furniture assembly, and electronics manufacturing.

3. Studs

Studs are threaded rods (often fully or partially threaded) that do not have a head, designed to be used in flanged joints, heavy assemblies, or applications where a bolt might not fit. One end of the stud is typically threaded into a component (like an engine block), while the other end has a nut tightened onto it to secure the joint. They provide a strong, stable connection because they distribute load evenly and can be tightened to precise torque specifications. Studs are commonly used in automotive engines (to secure cylinder heads), industrial machinery, and pipe flanges, where high clamping force and reliability are essential.

4. Nuts

Nuts are internally threaded fasteners designed to mate with bolts, studs, or threaded rods to create a secure joint. They come in various styles to suit different applications: hex nuts (six-sided, the most common type, tightened with a wrench), wing nuts (with two flat “wings” for hand tightening without tools), and acorn nuts (rounded to cover the end of a bolt for safety and aesthetics). Self-locking nuts have a nylon insert or deformed thread that prevents them from loosening due to vibration, making them ideal for automotive and machinery use. Nuts work by applying clamping force when tightened against the components being joined, and their compatibility with different bolt sizes and materials makes them a universal component in almost all industries.

5. Threaded Rods (Threaded Bars)

Threaded rods, also called threaded bars, are long, straight rods with continuous threads along their entire length. They are used for tensioning, anchoring, or as a base for building custom fastener assemblies. Common applications include securing structures to concrete (using anchor nuts), supporting heavy loads in construction, and creating adjustable joints in machinery. Threaded rods can be cut to specific lengths, and their fully threaded design allows nuts to be positioned anywhere along the rod, providing flexibility in how components are connected. They are available in various materials, including carbon steel, stainless steel, and alloys, to suit different load and environmental requirements.

6. Washers

While not always considered a “primary” threaded fastener, washers are essential companions to bolts and nuts, designed to protect components and improve the performance of threaded joints. Flat washers are the most common type—they sit between the bolt head/nut and the component surface to distribute clamping load evenly, prevent damage to the component (like scratching or denting), and create a smooth surface for the fastener to tighten against. Lock washers (such as split washers or toothed washers) have teeth or a split design that grips the surface to prevent the nut from loosening due to vibration. Other types include fender washers (large, thin washers for use on soft materials like plastic or wood) and spring washers (which provide tension to maintain clamping force). Washers are used in almost every threaded joint, from household appliances to large construction projects.

Threaded Fasteners vs Non-Threaded Fasteners

1. Joint Type (Temporary vs Permanent)

Threaded fasteners create temporary joints that can be easily disassembled with basic tools (like wrenches or screwdrivers) without damaging the components. This makes them ideal for applications where maintenance, repairs, or modifications are needed, such as automotive parts or machinery. In contrast, non-threaded fasteners (like rivets, nails, or welds) typically create permanent joints—removing them requires cutting, drilling, or destroying the fastener or the connected components. For example, rivets used in aircraft skins must be drilled out to be removed, making non-threaded fasteners better suited for applications where the joint will never need to be taken apart.

2. Clamping Force and Strength

Threaded fasteners excel at providing high, adjustable clamping force thanks to their interlocking threads and the preload created when tightened. This makes them suitable for high-stress applications like structural construction, automotive engines, and heavy machinery, where the joint must withstand extreme loads or vibration. Non-threaded fasteners, however, rely on friction, deformation, or adhesion to hold components together, resulting in limited clamping force. For example, nails hold wood together by friction between the nail and wood fibers, but they cannot match the strength of a bolt and nut in a structural beam. This makes non-threaded fasteners better for light-duty applications like hanging pictures or assembling lightweight furniture.

3. Adjustability

Threaded fasteners offer full adjustability—you can tighten them to precise torque specifications to achieve the exact clamping force needed, and you can loosen or re-tighten them if the joint becomes misaligned or needs modification. This is critical in applications like machinery, where precise alignment is essential for performance. Non-threaded fasteners, on the other hand, are generally not adjustable once installed. For example, once a rivet is crushed into place, it cannot be tightened further, and if the joint becomes loose, the rivet must be replaced entirely. This lack of adjustability makes non-threaded fasteners less suitable for applications where precision or flexibility is required.

4. Installation and Cost

Threaded fasteners can have more complex installation, as they require alignment with threads (to avoid cross-threading) and often need specialized tools like torque wrenches for precise tightening, which can be time-consuming in large-scale projects. They also tend to be more expensive, especially specialty or high-strength varieties. Non-threaded fasteners, by contrast, are quick and simple to install—nails can be driven with a hammer, and staples with a staple gun—making them ideal for high-volume or repetitive tasks. They are also generally more budget-friendly, which is a significant advantage for cost-conscious projects like packaging or lightweight assembly.

5. Versatility and Material Compatibility

Threaded fasteners are highly versatile, with options designed for almost every material, including wood, metal, plastic, and concrete. Self-tapping screws, for example, can tap threads into thin metal or plastic, while concrete anchors (a type of threaded fastener) can secure objects to concrete. Non-threaded fasteners have more limited material compatibility—nails work well in wood but not in hard materials like metal or concrete, and rivets are primarily used in metal. This makes threaded fasteners the better choice for projects that involve multiple materials or require a secure joint in challenging substrates.

How to Identify Threaded Fasteners?

Identifying threaded fasteners involves examining key features to determine their type, size, thread pattern, and material—all critical for choosing the right replacement or matching components. Start by identifying the type: bolts have a head and require a nut, while screws have a head and may tap their own threads; studs are headless rods, nuts are internally threaded, and threaded rods are long, fully threaded bars. Next, check the thread pattern: coarse threads (like UNC, Unified National Coarse) have fewer threads per inch (TPI) and are easier to assemble, while fine threads (like UNF, Unified National Extra Fine) have more TPI and provide better load-bearing capacity. You can measure TPI using a thread gauge or by counting the threads in one inch of the fastener. For size, measure the diameter of the threaded part (major diameter) with a caliper—bolts and screws are often labeled by this diameter (e.g., 1/4-inch bolt). The head style (hex, Phillips, flathead) and material (steel is magnetic, stainless steel is not) are also key identifiers. Finally, check for standards markings (like ASTM or ISO) on the head, which indicate strength and quality specifications.

Materials and Standards for Threaded Fasteners

The choice of material for threaded fasteners depends on the application’s requirements, including load capacity, corrosion resistance, and environmental conditions. Common materials include: Carbon Steel (affordable and strong, ideal for general use); Stainless Steel (SS 304, SS 316, corrosion-resistant, used in food processing and marine applications); Alloy Steel (high tensile strength, used in heavy machinery and automotive engines); Duplex & Super Duplex Steel (excellent corrosion resistance and strength, for oil & gas and chemical industries); and Nickel Alloys (Inconel, Monel, Hastelloy, heat and corrosion resistant, used in aerospace and chemical processing). All high-quality threaded fasteners are manufactured to international standards to ensure consistency and reliability, including ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials), ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers), DIN (German Institute for Standardization), ISO (International Organization for Standardization), and BS (British Standards). These standards specify requirements for material composition, thread precision, strength, and finish, ensuring that fasteners from different manufacturers are interchangeable and meet safety criteria.